Alina Gatina

Without horse boots in Cairo

Having bid farewell to my aspiration of working at the magazine “Continent,” I journeyed to Egypt to gather material on the remnants of Kipchak culture in Cairo and the reconstruction of Sultan Beibars’ mosque.

Initially, Cairo mirrored the enchanting yet unreal calm of a fictional Baghdad – bustling yet peaceful. I attained proficiency in everyday literary Arabic and forged significant friendships with students from our country, international students, a few local families, history and art teachers, Islamic architecture scholars, and some embassy staff. However, the winter of 2011 had come, and all my efforts were overshadowed by the fires smoldering on Tahrir Square’s cold cobblestones, as Cairo transitioned into a quieter, yet less peaceful state.

Had I been a war correspondent, that period might have heralded the beginning of good times for me.

In December of 2010, when I still was cherishing the dream of compiling a collection of essays on the Turkic influence on the Islamic architecture of Egypt (which I had plenty of material for), my friends and I were on route to the Arabic language exam, being held in…? There were eight of us in two cars.: Mukhit, Rustam, Dana – from Almaty, Aidamir from Derbent, a graduate student from Tehran, whom everyone called Pers, Marek from Warsaw, and an intern at the Mexican Embassy, Cesar from Mexico City.

With ample time before our exam, we decided to drive through El Arafah (“The City of the Dead”) to take some pictures of the Mamluk Sultan Qait Bey mausoleum and acquaint Dana and Rustam with the El Arafah area. It was my and Muhit’s idea. Aidamir, Marek, the Persian and Caesar said they didn’t care and would go anywhere, as long as it didn’t involve taking the subway.

Perhaps we should have chosen the subway.

The winding labyrinths of El Arafah harbored no danger from the dead, but rather from the living. As we approached the tomb of Kait Bey, we found our way barred by a group of eight, armed with stones and sticks.

They said to us: Oaf! Entu kulluku ukhrug milarabeya! (Stop! All of you, get out of the car!).

We all got out.

– Oafu heena alelheta, – said someone dressed like a Tuareg. – La mouche vischoku lelheta, vischoku leya. Edeku aiz ashuf edeku. Entu min? (Stand here, against the wall. Not facing the wall, facing me. Hands! Hands in front, so I can see. So? Who are you?)

Mukhith said: Ehna agyaneb…talaba. Enta aiz e minnina? (We are foreigners…students. What do you want from us?).

– Felus. Hauz e minnukum tani?! (Money. What else would we need from you?!)

Mukhith said: Ehna talaba. Ma fiche felus. (We are students. We have no money.)

– Entu talaba aganeb. Ul aganeb daiman maaha felus. (You are foreign students. Foreigners always have money.)

Mukhith said: Ehna begat maanash felus…uehna metahharin ala elemtahan. Liauehna maeruhnash fi elmad hayahsal lena mushkela maa elwiza. (We’re already late for our exam. If we don’t get there in time, we’ll automatically fail, which could lead to visa problems for us).

Touareg said: Ulau entu maditunish elfelus, hatelkuvuahalas alaiku. Maschi? (And if you don’t give me the money, I’ll kill you. OK?) and pulled out a knife. A beautiful Berber dagger.

– That’s it,” Mukhith said. – My negotiating skills are exhausted. Time to buckle up. Who’s got what? I got a hundred bucks. Mukhith looked at me.

– I got about the same, only in guineas. But I’m supposed to use it to buy horse boots tonight.

– You are, but you won’t, right? – said Mukhith.

– ‘Yes,’ said I. – ‘I’d better buy some health for myself.

– Not at all,’ said Aidamir. – I just sent everything to my parents yesterday. I have twenty pounds in my pockets.

– I have no cash on me, thank God, – said Dana.

The Persian said a hundred, maybe a hundred and fifty guineas.

– ‘And I’ve got a hundred,’ said Caesar.

– Three hundred and eighty-six,’ said Marek and shrugged.

When the Tuareg had stuffed our money into the pockets of his galabeya, he looked at Dana and asked what was shining on her hand. Dana turned to Mukhith.

– Say “esvera.”

– What’s that? – Dana asked fearfully.

– Just say it.

– Esvera,” she said, almost in a whisper. And then, realizing what she was talking about, she pulled down the sleeve of her sweater.

The Tuareg said: Hatiha (Give it to me).

– Maadarsh, – Dana would have said if she hadn’t been so scared. (I can’t.)

– Hati. (Come on.)

– Di hidaya. (It’s a gift.)

– Ue di sikina. (And this is a knife.)

Dana undid the bracelet and handed it to him.

– Thank you, dear, said the Tuareg in English, – I’ll pin it on my knife and tell everyone it’s a gift.

This excerpt might comprise a fragment in my autobiography, penned in later years, had I become a famous person.

Such narratives might leave readers breathless, tempting them to accept every word as the unvarnished truth. Yet, documentary prose, even with its commitment to truthfulness, remains prose. It weaves an artistic reality, sometimes at the expense of strict factuality. The events described herein anchor the milestones of my life, with the exception of the elaborated episode in Cairo’s “City of the Dead.” This particular scene turns the narrative from a straightforward report into a lively story.

Ernest Hemingway spent his lifetime transforming his biography into such a narrative, cultivating an image that captivated millions. His portraits, emblematic of an adventurous spirit, graced the walls of countless homes and offices long after he was gone. Hemingway’s exploits—from his bravery as a Red Cross nurse on the Italian front to his valor as a journalist in the Spanish Civil War—cemented his reputation as a man of fearlessness: a hunter, fisherman, soldier, boxer, lover, and explorer. The extent to which the Hemingway myth aligns with reality is a task for his biographers to decipher. Is the factual accuracy about the life of this literary giant, whose persona permeated his works, truly crucial? Perhaps to some. Yet, imagine if Hemingway had written his biography as he wished to be seen by others. A great literary work, but still documentary prose.

Almira Ismailova

January Travelogue

Sometimes to visualize something you need to describe the images as if they were happening in the present. In movies, this technique is called a flashback or MEMORY HIT // We’re walking to the shop with my mother, and I notice that the vacant lot where we used to herd cows as children has been filled with newer houses, all clad in some sort of red-brick armor. An entire street. My mother tells me that half of the Karashilik aul, which had been abolished, has moved here. This story has stayed with me.

An acquaintance of mine, when he heard about Karashilik residents, had a funny association. In the second season of SpongeBob there is an episode where Bikini Bottom is attacked by the Alaskan Bullworm and Patrick suggests moving the entire town. The Karachilikans seem to have succeeded, settling down in clusters , some even building houses in the new location using material from demolished old houses. The ‘succeeded’ part is probably a misconception, though: they left something important behind.

In the north, where I was born, in one region alone, about 30 small villages have been abolished between 2019 and 2021. Karashilik was no exception, and it disappeared from the country’s maps in 2019. People left here in search of a better life: those who were richer went to the city, while the rest settled in neighboring villages.

In the village, they live from paycheck to paycheck, taking out a loan every summer to stock up on coal, firewood, and animal feed. They incessantly watch Russian television, which is filled with propaganda. Especially in the northern villages, there is a strong nostalgia for the Soviet Union. It represents the dream of a better society, where everyone enjoys stability and life follows a plan. People do not realize that the price for this “stability” was the destruction of their ethnic identity and utter unfreedom. It is about this kind of nostalgia that represents a ‘disease of modernity’ (Svetlana Boym, “Future of Nostalgia”) that I decided to make my movie.

December, 2021. My filmmaker friend Christina suggested I apply to the Documentary Film School and introduced me to Dana, who later became my producer. At the time I had very little idea about documentary filmmaking, but I fit right in. To get the application approved, I had to make a teaser. I had a long way to go. The project then began under the title “Where I’m from”. One of the first lines I wrote was: “Where I’m from, they talk loudly and laugh gleefully, but are completely incapable of expressing feelings, or declaring love. Where I’m from, women know how to cut carcasses and shear sheep, and men are not above growing a flower and plucking a duck. Where I’m from, children are given a mark for life by a rooster pecking at their temple. Where I come from, it’s warm even when it’s -40C”. The lines are naive but sincere, and I still align my director’s cuts against them. And if I had to describe my homeland, it would be like this.

***

Sony HDR-XR 350 camera.

LED Filling Lamp

Continent A3 black tripod

Sony NP-FV50 Camera Battery

Sony NP-FV70 Camera Battery

Sony BC-TRP Battery Charger

Thermos

Sandwiches

Me

someone who dared to make a film[ND5]

4 January 2022.

I will take a moment to tell the story of the renaming of the capital. After more than thirty years in power, the first President Nazarbayev had to give it up in favor of the new President Tokayev in 2019. The new political figure has given the people hope for positive change. Tokayev, apparently in an outburst of gratitude to Nazarbayev, proposed to parliament that the capital be named after the first president. Parliament approved and in a few hours the city of Astana turned into Nur-Sultan. By doing this, Tokayev clearly demonstrated that it was not worth waiting for changes, but after the events of January (the Bloody January or Kandy Kantar) Tokayev’s policy seemed to have changed drastically, even a new political course “Zhana Kazakhstan” was proclaimed. Persecution of those who were the untouchables under Nazarbayev was now in full swing. Nazarbayev’s name was gradually erased from the public field. And already on September 17, 2022 the capital was again Astana. Now we see that these beautiful words did not mean much.

The plan was as follows. We will get to Astana, wait for three hours and take another train—which seemed like the cheapest way to get there at the time. My brother, a student, traveled with me. We had a long and boring ride in an open carriage smelling of sweat, ramen noodles and fish. Once I saw the conductor hiding something in the bottom of the carriage. Now I always imagine that there is a whole universe beneath our feet: a wormy sea in which a hot-smoked Balkhash stud splashes as it beats the thick substance with its powerful fins to swim, but it is getting denser and denser. And it’s getting weaker.

The children cried and asked for cartoons, but the Internet is a fragmentary phenomenon in our vast steppes. At night the children calmed down and began to live the usual “analog” life. And as midnight approached, they fell asleep, hiding behind a thick curtain . Everyone slept like a baby until morning. It was a sound sleep of those who had broken with civilization. Our train bumped along the tracks, and seemed to wander in the dreams of the people on it. I dreamed nothing that night.

5 January 2022. By 11 a.m., we had arrived in the capital, already buzzing with unsettling news from Almaty that rippled across the country. It was clear something significant was unfolding, certainly not the work of terrorists.

20,000 terrorists

Kantar is remembered by the lack of reliable information and the abundance of misinformation. In the conditions of the dead Internet, it was announced on TV that foreign terrorists were operating in Almaty. Propaganda told about militants, who cut off heads of military men and seized the airport. The state channels (others were not on air) showed a fabricated video of a man confessing that he was a paid robber and provocateur. It all looked like a falsification on the scale of the country.

Suddenly, the internet failed entirely. We needed to get from the new station to the old one, my brother limped beside me, nursing a broken leg, while I struggled with a bag of film equipment. Eventually, we hired a cab driver despite them demanding exorbitant fares. There was no choice but to comply. As we moved through the city, the January air felt thick with apprehension, the streets eerily empty. Reaching the old railway station, we learned that a state of emergency had been declared. Security checks were everywhere, passengers’ possessions scrutinized. Whispered rumors in the waiting room implied that our train might be abruptly halted in the steppe, leaving us stranded and forgotten.

Meanwhile, Christina from Almaty managed to reach us by phone. She was terrified. After she called, I went downstairs to get an extra bag of Chinese noodles. And some cabbage rolls. And biscuits. And something else that wouldn’t go bad fast. Our train was the last one to leave that day.

6 January 2022. We typically reach Sarykol around 4 a.m., calling ahead as we approach so Dad can meet us at the station. By 12, possibly earlier, we lost all connection. Our only hope was that the train would indeed stop at our station, allowing us to see the familiar moving silhouette.

I rushed into the chilly hallway with my bags as fast as I could. I always dreaded missing the three-minute stop and the chance to get out of the train. With nothing else to do, I found myself gazing at the floor, ice intermingled with coal dust. ‘Here,’ I mused, ‘the ice lies beside the coal, oblivious to the latent warmth within.’ As the sleepy conductor wiped the handrail with a grimy cloth, I realized we had arrived. We’re here.

7 January 2022. We’re here, but we’ve stepped into a different reality—a reality where everyone is confined to their homes, reliant on landlines for communication, and glued to the television for endless news of a world unraveling. Christina and Dana were scheduled to fly out on the 7th to assist with the filming. Unfortunately, due to the circumstances we’re all too familiar with, they couldn’t make it. With trembling hands, I picked up the camera for the first time, beginning to shoot, once a semblance of calm had been restored. I even managed to make it to Karashilik. Only three houses remain there for winter . We called on Kairbek, whose family only comes from the city for holidays. With a square shovel, he cleared a path to the schoolhouse door and unlocked the padlock. The door creaked open just enough to squeeze through.

The footage that remains captures the determination of someone who dared to document these moments, camera rolling as they squeezed through the narrow opening. Gasping for breath, as if the cold, knee-deep snow had claimed me, I felt an overwhelming sense of isolation. Unlike SpongeBob, who fought the Bullworm to save Bikini Bottom , I stood immobilized in the empty expanse of the village , too afraid to move. At that moment, frozen in time, I might as well still be standing there. And so, the film is named Ystyk Zher (Burning land).

// BACK TO PRESENT

Within me reside both the one who went to shoot school and the one left standing in the snow. In Jungian psychology, there exists an opposition between the concept of the self as the authentic self and the concept of the persona as a social mask. Bergman explored this psychological collision in the movie “Persona.” While the comparison might not be directly relevant, I’ll attempt to explain.

During my travels across the country amidst social cataclysm, I encountered a political self that resonated deeply with the political “self” of my people living in the shackles of fear. Simultaneously, I discovered a creative “self” endeavoring to forge a world where freedom isn’t an empty sound, where complex concepts aren’t simplified, and where trauma is experienced rather than silenced or replaced by another trauma.

This conflict isn’t about winners and losers; it represents a profound worldview gap within one people. I find myself immersed in this rupture, documenting this reality. Living within this divide is intensely painful for me, and I hope it will be easier for those who come after me. ‘Ystyk zher’ (Kazakh for ‘hot earth’) is a searing confrontation within myself and several generations of my compatriots.

30th January 2024

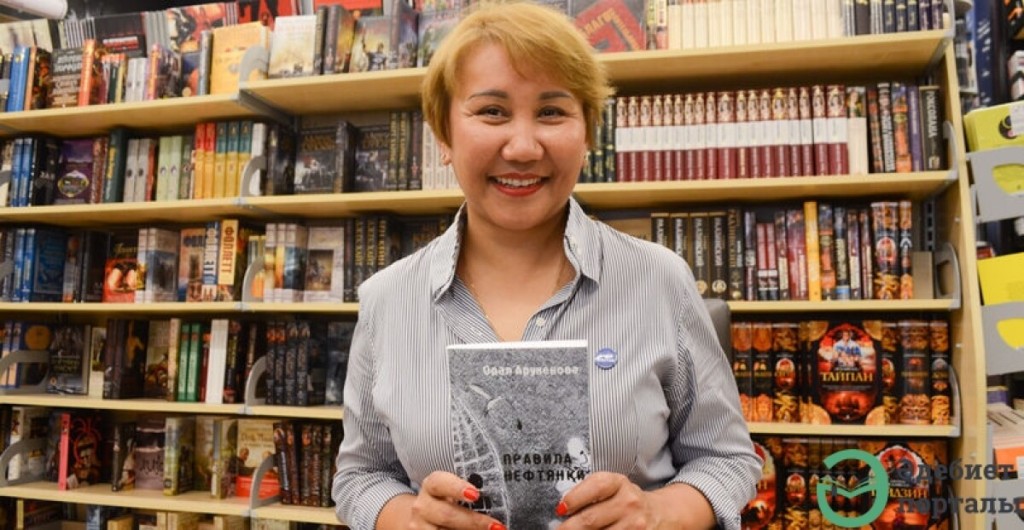

Alina Gatina is a novelist. She graduated from Al-Farabi Kazakh National University and the Literary Institute named after A.M. Gorky (the seminar of Oleg Pavlov). She is a laureate of literary awards such as the “Altyn Tobylgy”, “FIKSHN35”, and the “Friendship of Nations” magazine’s prize. In 2019, she launched her literary courses and now teaches an author’s course on writing skills. Alina was also a jury member of AWR-2021, the literary award Qalamdas. She works as an invited literary and managing editor at publishing houses in Almaty, preparing books for publication.

Almira Ismailova is a playwright, curator of the festival of contemporary Kazakhstani drama “Drama.KZ” 2019/2020, editor of the “Dramaturgy” section of the online journal “Dactyl”, and a documentary film director. Studied at the Yekaterinburg State Theater Institute specializing in “Literary Creativity”. She is a graduate of the theater and film dramaturgy courses at the Open Literary School of Almaty (OLSHA), the “Fundamentals of Film Dramaturgy” course at the Zhurgenov Kazakh National Academy of Arts, and the contemporary dramaturgy laboratory of Olzhas Zhanaydarov. She was a long-lister at the “Nim-2018” drama festival and the School of Documentary Film. Participated in the Central Asian Screenwriting Masterclass (CASL) organized by the UNESCO Cluster Office in Almaty as part of the “Strengthening the Film Industry in Central Asia” project. Almira is currently directing her debut feature film “Ystyq Zher” (Warm Earth).