A guest post by Nina Friess

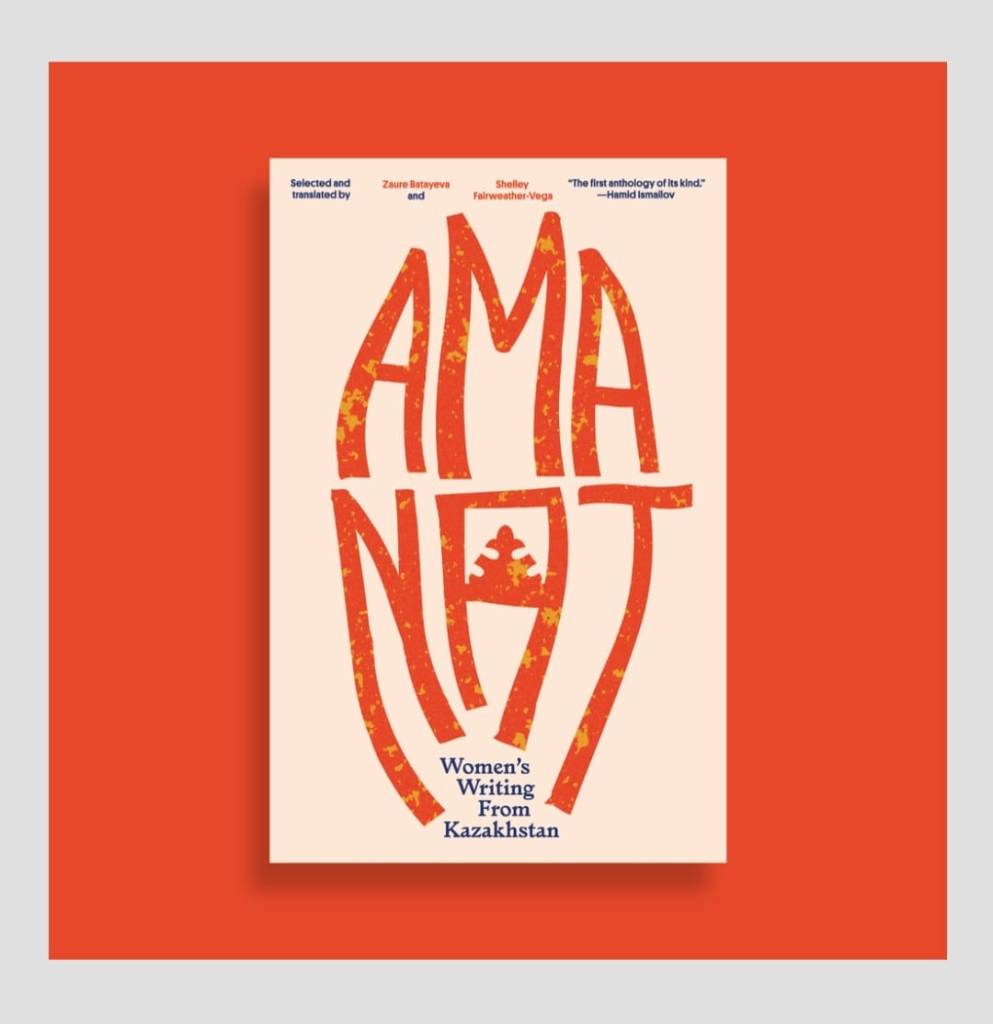

Right after the turn of the year, still in the midst of the pandemic, we were shaken by the violent takeover and ultimate bloody suppression of the initially peaceful civil protests in Kazakhstan. For a brief moment, the world looked at the largest Central Asian republic. I myself, who feared for friends and acquaintances in Kazakhstan at the beginning of January, was inundated with enquiries from German media about Kazakhstan’s literary and cultural landscape. But then Vladimir Putin let Russian troops march into Ukraine. Public interest in Kazakhstan, which had already waned considerably, disappeared and now focused entirely on Russia’s war against its sovereign neighbour, which violates international law. This is all too understandable. Nevertheless, I find it regrettable that it always seems to take extreme situations for ‘the West’ (and presumably other parts of the world) to engage with countries that lie beyond their own very narrowly defined cultural sphere. The publication of AMANAT, an anthology of texts by 13 female authors from Kazakhstan, published six months after ‘Bloody January’ by the New York City-based publisher Gaudy Boy, could be a great opportunity to explore Kazakhstan’s literature completely ‘disaster-free’. Carefully edited and superbly translated by Zaure Batayeva and Shelley Fairweather-Vega, this book is a unique opportunity to engage with Kazakhstan’s culture through literature.

The anthology comprises texts written by Kazakh female authors since Kazakhstan’s independence 30 years ago. It includes classic (short) stories, novel fragments and essays that could be described as anthropological. Humorous observations of everyday life are included in the volume as well as profound reflections on life itself (sometimes united in one single text, I am thinking here in particular of Lilja Kalaus’ story How Men Think), which can claim validity not only for Kazakhstan. It is true that readers can learn a lot about Kazakhstan’s recent history and culture from the stories, but – and Gabriel McGuire also writes about this in his foreword to AMANAT – it would be a shame to reduce the book to this transfer of cultural knowledge alone. (On a related note, I find the introduction by the editors and translators to be superb, as they provide the uninitiated reader with so much cultural context that he or she can easily make sense of the texts that follow).

Read more: AMANAT – female writers as the window to contemporary Kazakhstani literatureIs it worth noting that the texts are exclusively by female authors? Definitely. Because many of the authors, who belong to different generations, develop their stories around female protagonists who are underrepresented not only in contemporary Kazakhstani literature. Their fate and their view of life differ significantly from that of their male companions, whom they – and this is the theme of several stories – often outlive. This is particularly evident in the multiple dependency relationships which many of the female protagonists find themselves in Kazakhstan’s still patriarchal society. These are probably most shockingly depicted in the story 18+ by Aya Ömirtai, in which the female protagonist meets a man to to inquire about a job but instead becomes the subject of unwanted sexual advances. However, the protagonists in AMANAT are not only victims. For example, the just-abused heroine in 18+ sends a young man packing when he tries to molest her on the street. And the underage protagonist in Olga Mark’s The Lighter inverts the relationship of dependency when she blackmails her punter after completed sexual services in order to provide herself and other orphans with consumer goods. (Of course, this text is also an indictment of a society that allows such conditions). Oral Arukenova’s heroines are also strong women who assert themselves in a male-dominated world and casually demonstrate that Kazakhstan is also a modern country with successful businesspeople. This is particularly relevant to Western readers, whose image of Kazakhstan, if they have one at all, is often shaped by nomadic myths, which are indeed also cultivated by the Kazakhstani government.

What makes the anthology so special, apart from its content, is that it contains texts by female authors writing in Russian and Kazakh. Over the past 30 years, these two literatures have mostly developed independently of each other in Kazakhstan. Only recently have there been renewed attempts to bring these literatures into contact with each other, for example through the work of the online journal Daktil. AMANAT is an important contribution here, as the volume shows how much they have to say to each other. In my opinion, it would therefore be very desirable if a publisher could be found in Kazakhstan who would publish AMANAT in a Russian and a Kazakh edition so that the volume could also reach readers ‘at home’.

If one wanted to criticise anything about the anthology, which I find difficult, it might be that it contains only prose texts. Some of the most interesting literary voices of contemporary Kazakhstan – those of its female poets – are thus missing. But I remain hopeful that the poems of Oral Arukenova, who is represented in the anthology with prose texts, Zoya Falkova, Irina Gumyrkina, Kseniya Rogozhnikova, Aigerim Tazhi[1] and many others will find a place in another anthology.

[1] Tazhi is, however, one of the very few contemporary Kazakhstani authors whose texts were already published in English translation. In 2019, her anthology Paper-thin Skin was published by Zephyr Press, Brookline, Mass.

Nina Frieß studied political science and Slavonic studies in Heidelberg, St. Petersburg and Potsdam. She has been a researcher at ZOiS since October 2016. From 2009 to 2016, she was a research fellow at the Department of Eastern Slavic Literatures and Cultures at the University of Potsdam. In 2015, she completed her doctorate on the contemporary memory of Stalinist repressions. Her dissertation was awarded the Klaus Mehnert Prize of the German Association for East European Studies (DGO). In 2017, she completed her MSc in Science Marketing at Technische Universität Berlin. She is a co-founder of the project ‘Russophone Voices’, which explores current trends in global Russophone literatures and brings together authors, researchers and readers.

One thought on “AMANAT – female writers as the window to contemporary Kazakhstani literature”